One of the many ironies of Paradise Lost, John Milton’s retelling of the Book of Genesis as an epic poem, is Milton’s trashing of Calliope, the Ancient Greek muse of epic poetry. In Book 7 of the poem, he references Calliope’s failure in mythology to save her son’s life and calls her “an empty dream” (7.39). Epic poems need a guiding muse, however, so instead Milton invokes Calliope’s older sister Urania, the muse of astronomy, to inspire his tale. Urania full-heartedly answered that call if we’re to judge by all the beautiful descriptions of the cosmos in Paradise Lost: the sun is an “all-cheering lamp” (3.581), the stars that stud the firmament are “living sapphires” (4.605), and the Earth amidst it all is “hung by a golden chain, this pendant world” (2.1051-1052).

At times, Paradise Lost even seems to border on something like space opera: the angel Raphael hints at the existence of other worlds and extraterrestrial life, and Satan’s journey through the void to reach Earth is nothing less than an interstellar space flight. Milton was sometimes able to anticipate science fiction because of his engagement with the astronomy of his day, especially the new Copernican astronomy which laid the foundation for so much of SF’s interstellar fabulations. While I won’t go so far as to say that Milton himself was an SF writer, I do think we should at least acknowledge him as some kind of literary precursor: a space poet.

C.S. Lewis, himself a big fan of Milton who wrote extensively on his work, also recognized the beauty of Milton’s cosmology in verse. In his 1938 SF novel Out of the Silent Planet, Lewis even enlists Milton to help him describe the beauty of the universe. The reference comes as part of Lewis’ own remarkable description of the cosmos in Chapter 5. Having adjusted to the initial shock of being abducted onto a spaceship, his protagonist, Elwin Ransom, is surprised by how much richer the sun, stars, and planets now look, compared to the view from on Earth. Unlike the cold, empty void he’s been trained to expect, the cosmos is filled with ethereal light: “planets of unbelievable majesty” and “celestial sapphires, rubies, emeralds, and pin-pricks of burning gold” (22). The metaphors for the cosmos here follow some of Milton’s own, and I’m inclined to believe Lewis used him as a model.

Lewis caps off this series of Milton-esque descriptions of the cosmos with a direct quotation of the poet himself. His reasons for using Milton, however, are rather strategic. Lewis quotes Milton to illustrate a problem he had with the way modern people imagine space and with the very word “space” itself. Lewis writes:

But Ransom, as time wore on, became aware of another and more spiritual cause for his progressive lightening and exultation of heart. A nightmare, long engendered in the modern mind by the mythology that follows in the wake of science, was falling off him. He had read of ‘Space’: at the back of his thinking for years had lurked the dismal fancy of the black, cold vacuity, the utter deadness, which was supposed to separate the worlds. He had not known how much it affected him till now — now that the very name ‘Space’ seemed a blasphemous libel for this empyrean ocean of radiance in which they swam . . . No: Space was the wrong name. Older thinkers had been wiser when they named it simply the heavens — the heavens which declared the glory — the

happy climes that ly

Where day never shuts his eye

Up in the broad fields of the sky.He quoted Milton’s words to himself lovingly, at this time and often (22-23).

Lewis here takes to task his contemporary SF writers—especially H.G. Welles, whom he criticized as the case exemplar of what he termed “Wellsianity”—and their tendency to write the cosmos as hostile, amoral, empty, and fundamentally without a fixed purpose or meaning. The language here suggests an even deeper historical critique of the Copernican Revolution and how a sun-centered astronomy influenced the way humans think about our place in the universe.

To be clear, Lewis was not against heliocentrism or the scientific method in general, but rather against the anti-theological values and worldviews that modern people sometimes derived from such theories. Lewis wanted us to return to a more medieval way of imagining the cosmos, and Out of the Silent Planet is his attempt to show how modern astronomical concepts are compatible with that older mode of understanding. He wanted us to look at our heliocentric solar system cast amidst an unimaginably vast universe and relearn to see it as a beautiful play of creation, rich in meaning, and marked everywhere by the signature of its creator: “the heavens” as opposed to “space.” Lewis quotes verses from John Milton’s Comus at the end of this passage, and by so doing, he recruits Milton as the great poet of that older cosmological tradition.

Lewis could not have realized, however, how deeply ironic his choice to quote Milton was. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, Milton is one of the first writers on record and the first creative writer we know of to use the term “space” as a name for the cosmos. The OED quotes a line from Book 1 of Paradise Lost where, shortly after being banished to Hell, Satan proposes a change in strategy to his followers. Instead of attacking Heaven directly, he proposes to get revenge by corrupting God’s future creations. Satan alludes to these possible future creations with the ominous line, “Space may produce new Worlds” (1.650).

The line taken in isolation could have provided room for someone like Lewis to defend Milton. It is after all literally Satan who says this and who, fresh from his defeat in heaven, is looking for any way possible to undermine God. Perhaps Satan describes new worlds popping into existence out of empty space out of spiteful refusal to even acknowledge the author proper of their creation. Is it Milton’s fault that we modern dummies decided to take Satan’s blasphemy as a proper name for the cosmos? This hypothetical defense falls apart, however, when we dive a little deeper and see that this neologism doesn’t just reflect Satan’s spitefulness, but also the broader cosmological concepts underpinning Paradise Lost.

Milton’s cosmology draws from a wide variety of sources that sometimes even contradict each other. This is not surprising since Milton lived at a time when the ideas of the Copernican Revolution were still hotly contested, and he proved willing to borrow ideas from both the older tradition of an earth-centered universe as well as the new astronomy rapidly coming into currency. For example, Milton explicitly refers to the Earth as being the center of creation (7.242) and occasionally talks about the stars and planets as embedded in crystal spheres (3.416, 3.480-483), an idea closely associated with the geocentric model. There are other passages, however, where Milton almost seems to suggest that the sun, not the Earth, orders the dance of the heavens (3.572-81). He even goes so far as to entertain the notion of some of the most radical Copernicans that the stars, instead of just being lights embedded in the outer most sphere, might be entire separate worlds and even host their own forms of life (7.620-623).

As if in response to this contradictory material, there’s even a section in Book VII where Adam and the archangel Raphael directly discuss the merits of the heliocentric versus the geocentric models. Raphael entertains Adam only for so long, however, before warning him that God’s ordering of the cosmos is too complex for humans to understand. Raphael cheekily suggests that God might have even made the cosmos purposefully complex just so that he could have a laugh at Adam’s future descendants trying to figure it out (7.713-715).

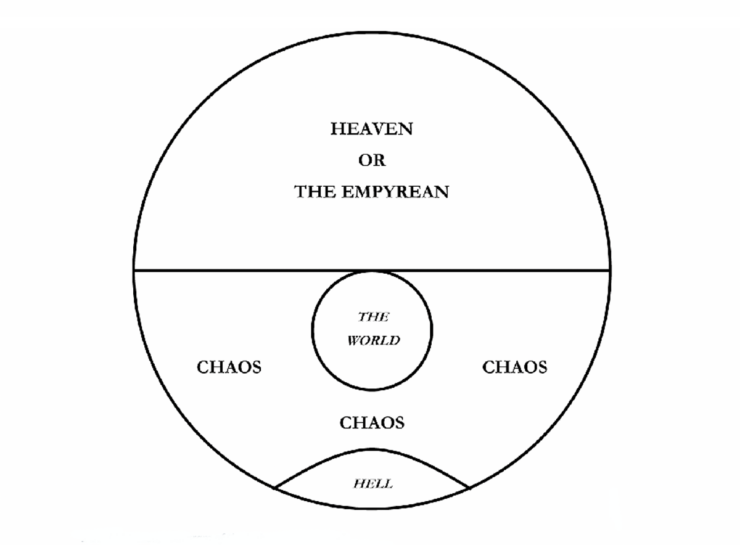

Leaving aside his ambivalence towards the heliocentric / geocentric question, there’s one significant way in which Milton was unambiguously a Copernican: his representation of physical space. To help explain what I mean, it will help to look at a layout of Milton’s universe.

Milton sets the observed universe of Earth, the planets, and the stars inside one vast physical space which also contains Hell and Heaven proper (‘Heaven’ here meaning the literal dwelling place of God and the angels). Milton’s universe also contains a region called “Chaos” or “Ancient Night.” Milton describes this region as

[T]he hoarie deep, a dark

Illimitable Ocean without bound,

Without dimension, where length, breadth, and highth,

And time and place are lost; where eldest Night

And Chaos, Ancestors of Nature, hold (2.891-895)

In Paradise Lost, Chaos is the primordial space from which God cut out Heaven, Hell, and our universe. This original, undifferentiated, infinite space didn’t just go away after the world was created, however, but remains a looming vastness in the backdrop—Satan in fact has to transverse that vastness in order to get from Hell to Earth. It is within this gargantuan ambient space that creation plays itself out: a small aberration, and perhaps even just a temporary one. Milton at one point ominously describes Chaos as “The Womb of nature and perhaps her Grave” (2.910).

This idea of the universe existing inside an unspeakably vast space in which our Earth is but a speck is completely alien to older cosmologies. Aristotle, as a prime example, describes his universe as a relatively small series of crystal spheres outside of which there was literally nothing, not even empty space since Aristotle didn’t believe a vacuum was possible in nature. Milton’s Chaos meshes very well, however, with the new ideas of space proceeding from Copernicanism. Copernicus demanded orders of magnitude more distance between us and the stars to make the heliocentric model square with observational data (namely the lack of stellar parallax, for anyone interested). The unprecedented freaks of scale demanded by heliocentrism prompted scientists and philosophers to start asking whether space might be not just merely titanic, but infinite, and how much of that space could be empty vacuum. Chaos in Paradise Lost is correspondingly described as both infinite (7.168-169) and often as an “abyss” or “vast vacuity” (2.931).

This new Copernican concept of space doesn’t just enter Milton’s cosmology, but also serves to blow up his angels. When we first meet Satan and his crew in Hell, Milton labors to convey just how big they are. Satan’s shield, for example, is described as having “Hung on his shoulders like the Moon, whose Orb / Through Optic Glass the Tuscan Artist views” (1.287-288). “The Tuscan Artist” here is a reference to Galileo Galilei, whom Milton actually got to meet once when he was a young man. The inclusion of Galileo and his telescope in the simile suggests that not only is Satan’s shield as big as the moon, but we humans must resort to the science of astronomy to help us appreciate just how big that really is, in the grand scale of things. It’s almost as if Milton is saying that epic poetry by itself is not enough to grasp the magnitude of Satan and the universe he inhabits; we need to call on Urania.

C.S. Lewis was not entirely wrong to enlist Milton as a poet of the heavens. Milton was deeply read and imaginatively invested in the old Pre-Copernican astronomy, and, like Lewis, his mission was to show humans where they fit into God’s universe, whether heliocentric or geocentric. Lewis’ great error was in trying to make Milton a poet of only the heavens. Paradise Lost is a historical snapshot of heliocentrism gradually displacing medieval cosmology in the Western imagination, and Milton grappled with the ramifications of the Copernican model. He was one of the first great poets to really face the dawning knowledge of just what a small place we hold in the universe and to ask what the implications of that were for human destiny. To render him into some kind of token of medieval naiveté is an insult as well as an anachronism. Milton was a poet of the heavens and of space; he may have held on awhile to the little crystal universe of Aristotle and Ptolemy, but in the end he could not help but to drop it into a vast, dark sea of Copernican night.

Works Cited

Lewis, C.S. Out of the Silent Planet, Samizdat, 2015.

Masson, David. Diagram of the Universal Infinitude, 1874.

Milton, John. Paradise Lost, Global Language Resources Inc., 2001.

“Space, n.¹, sense II.i.8.” Oxford English Dictionary, https://www.oed.com/dictionary/space_n1. Accessed 1 August 2023.wq

A.J. Rocca is a writer and an English teacher from Chicago. He specialized in the study of speculative fiction while pursuing his M.A., and now he writes both SFF criticism as well as his own short fiction. You can find his collected work here and connect with him on The Website Formerly Known as Twitter.